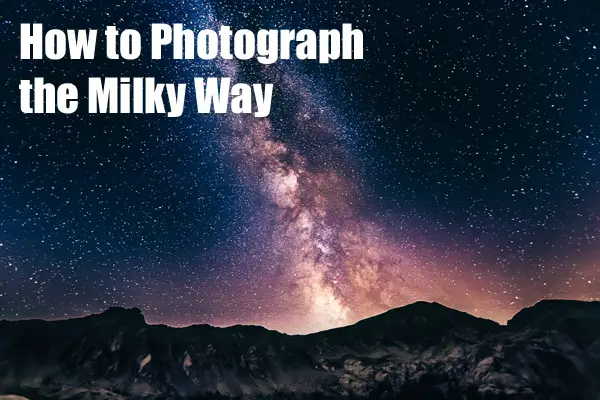

Taking pictures of the heavens can be tricky. Not only do you need a fast camera, but you also need a clear night sky.

This can be a tough situation to achieve, as not only are you up against the weather, but you also have light pollution and a number of other factors that can all contribute to making your night time photography session fail at the first hurdle.

But let’s not worry about those factors too much. In this new series, I am going to teach you the skills and techniques all needed for any kind of late-night photo session, from the stars to the moon and even our own galaxy!

But before I do that, you need to make sure that your kit bag has the following:

- Sturdy metal or heavy graphite tripod

- Camera release

- Stopwatch

- Wide angle lens

- Compass

- Star chart

You’ll need a good heavy tripod because, in order to shoot in complete darkness, you’ll need to set your camera at a very long exposure, such as 30 seconds or even more, depending on how dark the night is.

You’ll need a camera release to ensure that no unwanted pressure is set upon the camera when pressing the camera’s trigger. Ideally, you want one where the trigger can be fixed.

You’ll also need the stopwatch to work out your exposure time if you need the camera’s shutter to be open beyond 30 seconds. Taking photos at night can be a long, played-out process, so ensure you also pack lots of warm clothing so that you don’t catch a chill.

A wide-angle lens, useful when shooting a landscape, is a great bit of kit that will give the sky the breath it needs to bring the image to life. However, avoid straight-on shots of the moon with a wide-angle lens, as it can make the moon appear warped. Lastly, a compass and star chart are needed, so that you can locate the positions of certain constellations at the different times of year and the north star.

When to Shoot

It is a common misconception that shooting during the summer months will give you a clearer night. This actually couldn’t be further from the truth. A clear winter’s evening is far clearer than the summer because you have less particles in the air, such as dust and pollen that can make a haze or even further intensify light pollution. The sky varies in its levels of darkness throughout the year. With this in mind, the best times to shoot for each month are as follows:

- March, 3am

- April, 2am

- May, 1am

- June, Midnight

- July, 10pm

- August, 9pm

- September/October, 11pm

Shooting late in November, December, January and February, if you’re living in the northern hemisphere, I’d advise that you wait a few months until the weather gets warmer. Unless, of course, you can’t wait to shoot during these months and have a very thick coat, in which case…

November/December 1am

January/February 3am

What Would You Like to Shoot?

As I mentioned above, there are a number of options other than just shooting the stars. The most impressive of these has to be the band of our galaxy that is visible on a clear night, called the outer edge of the Milky Way, which is notoriously tricky to shoot. However, here’s how you capture its allusive majesty:

Location, Location, Location, Location…What’s Next? That’s Right! Location!

You need to find a location that has little or no light pollution in the direction of your shot. This can be extremely hard to find, but in a way is half the fun! A rural area is by far the most desirable, but make sure the Milky Way is not in the direction of a town or city, Otherwise, the light pollution will get in the way, making your image orange and ultimately…ugly.

How to Find It!

The brightest part of the Milky Way is towards the direction of Scorpios/Sagittarius. Look for those constellations on your star chart and take note of the direction where you need to point the camera and the best time of the night to do it. This will be when the constellations are higher in the sky.

You need to avoid star trails unless you actually want some or are lucky enough to get some that work well with your composition. In all fairness, though, you have as much chance as being hit by said meteorite! Use a very wide lens, a fast one if you have it and a solid tripod with a good ball head.

The Procedure

Many photographers, when shooting a subject as difficult as our galaxy’s outer rim, follow a set of practiced and rehearsed procedures in order to ensure the best results. Here is my own, which in time you’ll no doubt change to suit your style, but for now, here it is as a base from which you can develop:

First Stage: Framing

– lens wide open

– ridiculous ISO (12800,25600 etc)

– 2 or 4 second exposures

Use these short exposures moving the camera around to find the framing you like. The photos are useless, but we are using the camera as an extra pair of eyes, eyes that are far more sensible to the light than ours.

Once the framing is found, we move to stage 2, the exposure.

Second Stage: Exposure

– lens wide open

– ISO800 or 1600

– 20 seconds exposure

Take a shot, and in the camera LCD, examine the stars near the borders of the frame (not the center). If you see trails, then repeat with a shorter exposure. If you don’t see trails, repeat with a longer exposure. Do this until you find the longest exposure you can afford without trails.

Top Tip: When you check the stars for trails, you might see the stars at the borders display a strange, triangular shape. That’s called “comma” and is an optical defect on the lens. To solve that, close the aperture 1 step (for example, move from F2 to F2.8). Some lenses are good at F2.8, others at F4 and others around F5 for night time photography.

Following these steps, you will get a shot with a framing you like and the longest possible exposure time without trails or optical defects. That’s your Milky Way photograph!

The Milky way moves throughout the night, so don’t be alarmed if it shifts from a vertical position to a horizontal one. This is due to the Earth moving and can cause you problems if you fail to take this into account. However, providing you’re aware of it, it shouldn’t pose as too much of a problem.

The Milky Way, when shot in panorama, looks amazing, and, provided you are sure to allow around 40% overlap between each image, your stitching software should cope and bring the image together well.

If you’ve taken any shots yourself or happen to have any questions, please do leave them in the comments below along with links to your work, as myself and all the other fellow Photodotoers would love to see your work! And remember to keep your eyes peeled for the next part in our shooting stars series next week!

I like Photograph the Night Sky

Hi Robert, thanks for the informative article, would it be possible to obtain the the best time and locations for the southern hemisphere.

thanks for the information,,, lovely photos 🙂

Very informative article with lots of tips and insightful techniques – well done! But wait, there’s more – I can hardly wait to see Part 2…

The effect from few nights ago! I am really hooked and am looking forward to taking some more photos of stars. This is in Queenstown in New Zealand btw.

thanks for the tips. I was wondering what your opinion is for using fisheye lenses for milky way shots.